I regard each photo my father took before stuffing it into the bag, and when the bag is full I jiggle the contents around so I can cram more in. Her face bobs up out of the flotsam, a smiling stranger. Instead of pushing her down, I edge more of the picture out. She's young and quite lovely, looks intelligent. Instead of pushing her down, I arrange her just so, get my camera, and take her picture. Then I continue to fill up the bag.

My father took all but two of the pictures, so when I come across a photograph of him peering down into his Rolleiflex, I pause. I guess he's just taking a light reading, but he's standing in an open field, dressed in his habitual suit and tie, with elegant cufflinks, and at first glance he seems to be taking a picture of a paper bag. His face is barely visible; it's clearly another throw-away picture. I shove the photograph into the bag and observe the way he seems to pop out, like a jack-in-the-box. I get my camera again. This time I photograph my father in the bag, photographing a bag.

And then I give in.

And I take out all the pictures, one by one.

This is my father's profile. Without a doubt, this is my father's shadow. See how textured his shadow is, with long, dry grass and pebbles embedded in the hard dirt? Feel the blackness bristle? It's a picture of my father, but also a picture of his absence. The index finger lifts—to beckon, to point, to pause? A vaporous shadow wafts from his head like the mist of a migrating soul, escaping in wisps, like thought or heat. Breath, life. But it's just a tree casting a dappled shadow.

It's tempting to rearrange the photographs to resemble a clear narrative. This man has a boring face but he's so attractive. His mouth, and the proportions of each feature to the others, the precise way his ear is poised above his jawline, a pictograph of listening, directly across from his flared nostril, breathing. The way the fleshy chin, below, balances his bristling hair and sharp gaze, above. A gaze that penetrates something we can't see. (The thought forms, No one has ever looked at me that way.)

I might be tempted to put these pictures last, the sharp photo followed by the overexposed one. Suggesting, perhaps, how we fade away, but also how we endure. But then the impact of this tide of images would diminish. Its force comes from its mystery, the collection of apparently random moments.

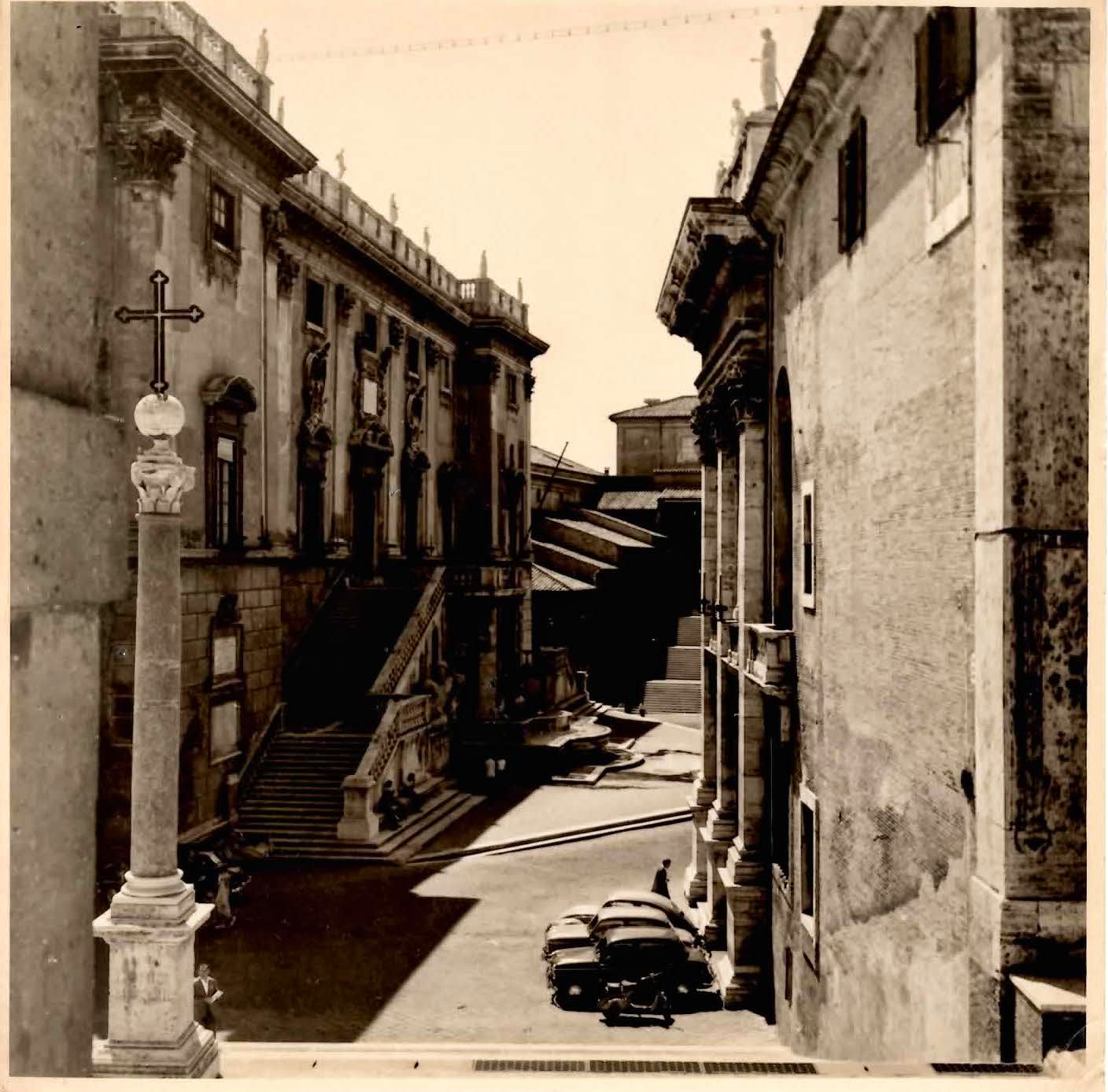

In black-and-white, sculpture looks more natural in its surroundings, no longer incongruous, as if a nude old man were really reclining on a boulder in the middle of a plaza, thinking hard about something, disinterested in passersby. The scalloped curtains hanging in the balcony windows contrast with his bare flesh, making the old man appear more naked and alive, and the windows more empty.

I'm not sure, but this may have been the dilapidated villa where my father and his students stayed while they studied art history in Rome. It hardly matters to me, those details I miss. Never mind that I don't know the story of the house or its inhabitants. That's the part of the wreckage that sinks first. What floats to the surface is just this moment in life when my father paused. When we see what he saw.

This may or may not have been the pet goose of my father's first wife, in Italy. It's purpose is fading, out of context, or maybe it's being restored to a purer existence, free of association. But that's a lie. As long as there is someone to look at it, it will mean something. It's a picture of a goose and a moment in my father's life which has passed, but which we can still experience in this form. Like the way a star's light travels to us long after its death.

Spanish moss hangs from the trees on Ossabaw Island, catching most of the light. Although the trees' growth is slowed, they manage to survive anyway, quite beautifully. Spanish moss isn't parasitic, nor is it really a moss or even a lichen, but something called an epiphyte, which is rootless and takes its nourishment from air and rainfall. The Latin name, which might have mildly interested my father, as a Latinist, is Tillandsia usneoides, but it's more commonly called 'air plant.' A home to rat snakes, several varieties of bats, and jumping spiders. Such facts were uninteresting to my father. What interested him was a different kind of drama—not nature, but something resulting from his own interpretation.

Charlotte, love, you keep amazing me.

ReplyDeleteEnchanting...

Charlotte...this is utterly perfect.

ReplyDeleteDon't throw them away. Send them to me. I'll keep them among the 'Golden Apple' essays! Did I tell you he lectured to my class and one slide popped out of the projector and we never found it again. It was the one he's specially paid to have taken, of the under view of the Boy with the Thorn that had been in the Piazza San Giovanni.

ReplyDeleteJulia, you're saving us—you make me cry. I would like to really, physically hug you. My dream is that if I really do make it to Taormina this spring with my sisters, if it happens to be convenient for you, I might find a way to visit you for a day or two. With the pictures, and hugs...That naughty underview of the Thornpuller and his painful self-discovery...How he must have enjoyed telling a whole class!

Delete